I’d like to rename this mid-October time of year Walking Season. If you came Upstate this week you’d be surprised to find vacationers overspilling every lane. They’re two abreast in Woodstock’s Tinker Street and hikers and their cars crowded the road in front of Panther Mountain til it was nearly impassable on a weekday afternoon.

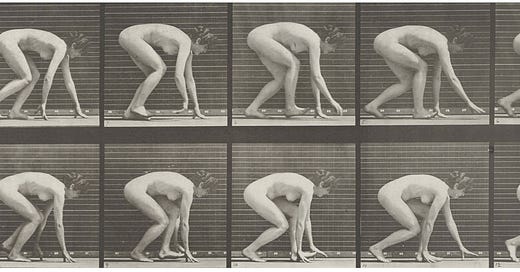

The word ‘cadence’ very tidily and poetically binds my thoughts on writing, mid-autumn and walking. Cadence is a “flow of rhythm in prose or verse,” of course, but its roots are grounded in the Latin cadere, “to fall,” in the way a voice rises and falls, and each foot fall follows the last, but also the way chance and fate befall us all. And maybe the way the leaves fall, too.

There’s nothing that boosts creative practice like walking, besides, perhaps, the act of committing to the work itself. Walking builds a satisfying rhythmic feedback loop—a cadence—that entrains the body and its thoughts with each step. As French poet Paul Valéry noted, while walking and thinking “there is a certain reciprocity between my pace and my thoughts—my thoughts modify my pace; my pace provokes my thoughts.” A great legacy of writing walkers informs the connection, including evangelizers like Henry Thoreau, for whom walking was “a sort of crusade,” but also poet Frank O’Hara, who took a work-a-day view:

“It’s my lunch hour, so I go

for a walk among the hum-colored

cabs…”

I was among the big-destination walkers this week, scrambling up a rocky mountainside to marvel at the light in the leaves. I climbed in the footsteps of Dorothy Wordsworth, sister to poet William, and well-known for her intrepid ascent of Scafell Pike on October 7, 1818, a bold and eccentric feat for a woman at that time. More spectacularly still, however, the Wordsworth siblings built their lives around blocks of walking, hiking every morning for two hours, but also pacing in the garden every evening from 4:30pm til 6pm for four decades. As they walked or paced they hummed and murmured lines of poetry, to themselves or to each other, friends reported, musing, rhyming, strolling up and back. It was a life worth living. As Dorothy wrote in her journal in 1802: ”I went and sate with W. and walked backwards and forwards in the orchard till dinner time. He read me his poem, I broiled beefsteaks. After dinner we made a pillow of my shoulder — I read to him and my beloved slept. I afterwards got him the pillows, and he was lying with his head on the table when Miss Simpson came in. She stayed tea. I went with her to Rydale — no letters! A sweet evening as it had been a sweet day, a grey evening, and I walked quietly along the side of Rydale Lake with quiet thoughts — the hills and the lake were still — the Owls had not begun to hoot, and the little birds had given over singing.”

…the Wordsworth siblings built their lives around blocks of walking, hiking every morning for two hours, but also pacing in the garden every evening from 4:30pm til 6pm for four decades. As they walked or paced they hummed and murmured lines of poetry, to themselves or to each other, friends reported, musing, rhyming, strolling up and back. It was a life worth living.

Destination-driven walks are one thing, but Dorothy’s description of her arrival at Scafell’s summit, incorporated unattributed into her brother’s account in his Guide to the District of the Lakes, focusses not on the vastness she found there, but on the stones, “which cover the summit & lie in heaps all round to a great distance, like Skeletons or bones of the earth not wanted at the creation, & here left to be covered with never-dying lichens, which the Clouds and dews nourish; and adorn with colors of the most vivid and exquisite beauty and endless in variety…” I like to think her regular localized walking practice allowed her to see the details she might have missed if she’d been transfixed by the bigness of the view.

From a physiological perspective, walking is a panacea. Walking can help a blocked artist or writer thaw a freeze response to their work, as I’ve seen in my own coaching practice. Fascinatingly, research shows that merely being indoors inhibits the release of dopamine. So that energizing potency of pursuit is available anytime you venture past the doorstep. Studies have demonstrated that walking stimulates cognition, with those who took a 35-minute walk outside—whether in a forest or on the city streets—performing higher on cognitive tests (walking in a natural environment granted more benefits between the two).

Another study asked participants to generate analogies. Those who walked beforehand—for between 5 and 16 minutes—recorded a 95% success rate in coming up with at least one “high-quality analogy.” The control group sat indoors and was able to complete the task 50% of the time.

Writers, do you hear that? A five minute walk can increase your odds of writing something good by a whopping 45%. (Not walking before you write is like leaving a party before they serve cake, a decent, but not necessarily high-quality analogy that Nico and I came up with after a 7 minute walk.)

Walking also provides entry to a zone researchers call “deliberation-without-attention,” a mind-state induced by performing a repetitive task that pulls at least some of your attention away from a more complex problem at hand. Rather than over-focussing on your issue, which doesn’t leave room for subconscious input, your shifted focus allows the unconscious to silently slide in with more fresh perspectives and new lines of thinking.

Though people are suspicious of pacing—too frenetic, too comic, too neurotic—I think it, too, may be an underutilized tool. Studies have shown that pacing provides the kind of repetitive movement that soothes stress, in part by feeding the brain predictable patterns that it loves. (Pacing is especially effective for supporting anyone with ADHD signatures.) I like this cold-cut type of walking, pacing the garden or, as I used to do at our old place, creating a super familiar localized loop down and around the park at the end of our street, which took me 8 minutes exactly door-to-door. I used to walk it between calls. So, this week I’m re-invigorating that practice, establishing a circuit around the front and back yards at our new place. I walk up, around and back. The leaves twirl and fall. The sounds of words form in my mind and create a cadence and a hum in the fading light, echoed by my pace, weaving an ordinary and extraordinary connection between my interior thoughts and the outer world.

“We walked backwards and forwards till all distant objects, except the white shape of the waterfall and the lines of the mountains, were gone,” Dorothy Wordsworth wrote in her journal. “We had the crescent moon when we went out, and at our return there were a few stars that shone dimly, but it was a grey cloudy night.”

Drop a comment below if you experiment with walking, working and falling into a new cadence this week. XJessica

Walking in Time

British land art pioneer Richard Long’s first major work was created while he hitchhiked his way from his home in Bristol to London, where he was a student at St. Martins. Between lifts, he paced a line in a country meadow, until he had etched a path into the ground and photographed it. His celebrated work “A Line Made By Walking,” bridged performance and sculpture in an energizing new way. Long went on to create walking pieces in Peru, in Bolivia, in Death Valley, California and in Nepal. In 1998 he walked for 33 days, 1,030 miles from the southern tip of the British mainland to the northernmost point, each day placing one stone along the way. “The significance of walking in my work is that it brings time and space into my art; space meaning distance,” the artist has said. “A work of art can be a journey.”

Beyond the philosophical, however, Long’s investigations are also somatic. "My footsteps make the mark,” Long explained. “My legs carry me across the country. It's like a way of measuring the world. I love that connection to my own body. It's me to the world.”

Beneath Rhythm

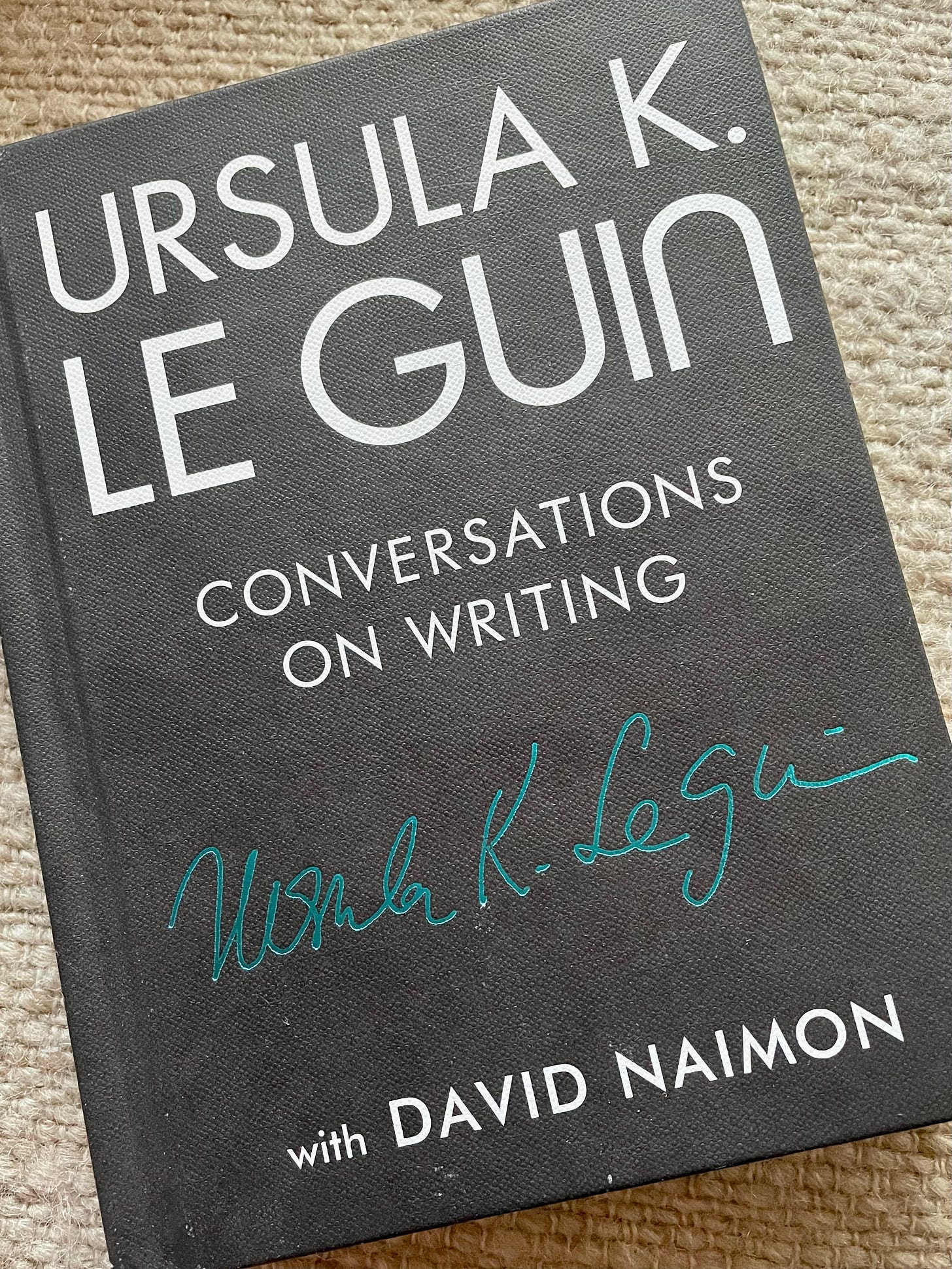

I haven’t read enough of this book to recommend it yet, but I opened up to this quote today and it’s too perfect:

“Beneath memory and experience, beneath imagination and invention, beneath words, there are rhythms to which memory and imagination and words all move. The writer’s job is to go down deep enough to feel that rhythm, find it, move to it, be moved by it, and let it move memory and imagination to find words.”

Walking could help catalyze it all.

Resonance here: https://atmos.earth/benefits-of-walking-and-thinking

Jessica, I saw you had liked Micheal Easter's post and checked you out. I'm glad I did! I'm a huge fan of walking and write about it (and rucking) frequently. I am a big believer in the words of St. Augustine's 'solvitor ambulando.' Each week I share a post with my reader's. I'd love to share this one next week. Thanks!