Scenting fall

What is the smell of autumn leaves?

I’m stopped on the forest trail, hands full of crisp autumn leaves that smell perfectly leaf-like. “Toasty,” I venture. ”Sweet?” I don’t like this game of coffee roasters and sommeliers.

Most often the way we describe scent is determined by cause or effect. Cause: wet grass, coffee grounds. Effect: appetizing, nauseating, etc. We dredge up memories. We try metaphor, simile, comparison, or even metonymy. In centuries past, writers used more intriguing scent words: incensial, odorant, redolent, pulvil, fetid, rank, miasmatic, putrescent, effluvia. (Originally “flair,” meant “odor,” but came to describe hunting dogs with a ‘flair’ for scenting hare.) Yet even 18th century cultural critics disparaged literature’s general refusal—or incapability—to describe scents in English.

Some thinkers devised systems. In 1857 English perfumer Septimus Piesse created a musical scale describing aromatic harmonies, introducing the word “note” to the pursuit. In 1916 German philosopher Hans Henning debuted his smell prism, corners distinguished by six primary aromas. In Henning’s system, autumn leaves would be found along the fruity-to-putrid edge, I suppose.

Others focused on the molecular structures of odor-producing substances or looked into chemosensory and neuroanatomical studies to explain the way we perceive them. And so off I go, learning that autumn leaves turn color as their chlorophyll breaks down, green dissolving to reveal reds, golds and oranges hidden there all along. Fungi and soil bacteria, especially geotrichum candidum, digest the fallen leaves and their sugars, releasing terpenes and isoprenoids, gaseous compounds that make that musty, toasty, sweet smell.

I’m more intrigued, however, by a recent “biopsychosocial” study of the forest and its smells, including its impact on spiritual wellbeing. Researchers in the UK sent participants into Sherwood Forest on afternoons throughout the year, asking them to record what they noticed, whether colors, textures, sounds, shapes or smells. Using words like “musty,” “decay” and “foliage,” participants generated 337 mentions of smells, compared with 223 for sound and 596 for color. Most interestingly, however, the subjects noted more smells in autumn than in any other season, but they also ranked their autumnal jaunts as the most beneficial by far—in every category—physical, emotional, cognitive, spiritual and global.

So, let this be a beckoning call that brings you to your local Sherwood. This week I’ve been getting into the woods as often as possible to savor the scents. Tipping my chin like our dog, Rue, nose to the sky and air passages open to the maximum, I’m especially free of the false assumption that humans are bad at smells, an archaic colonist/capitalist/Kantian notion based on that old fear of our animalistic nature. In fact, I’m quite good at smelling things. So are you.

In the end, however, the scent-identifying parlor game leaves me cold. Instead, I believe in the intrinsic rightness of the smell of autumn leaves, the goodness of this moment, the way it evokes those times when I was a kid buried chin-deep in a leaf-pile. I’m awed by the ways aroma connects me to the season, to the land, and to other creatures scenting and sensing it. And it all makes me glad and grateful to be alive. Why force more by insisting on distracting, unsatisfactory adjectives?

As pure experience my leaf-scenting settles inside, far from graphs and chemo-classifications, where it can decompose into a sub-verbal, sweet-scented matrix to infuse my soul and my self with a scent beyond words, in mystery. I am sure it is medicine.

Autumn Vibes

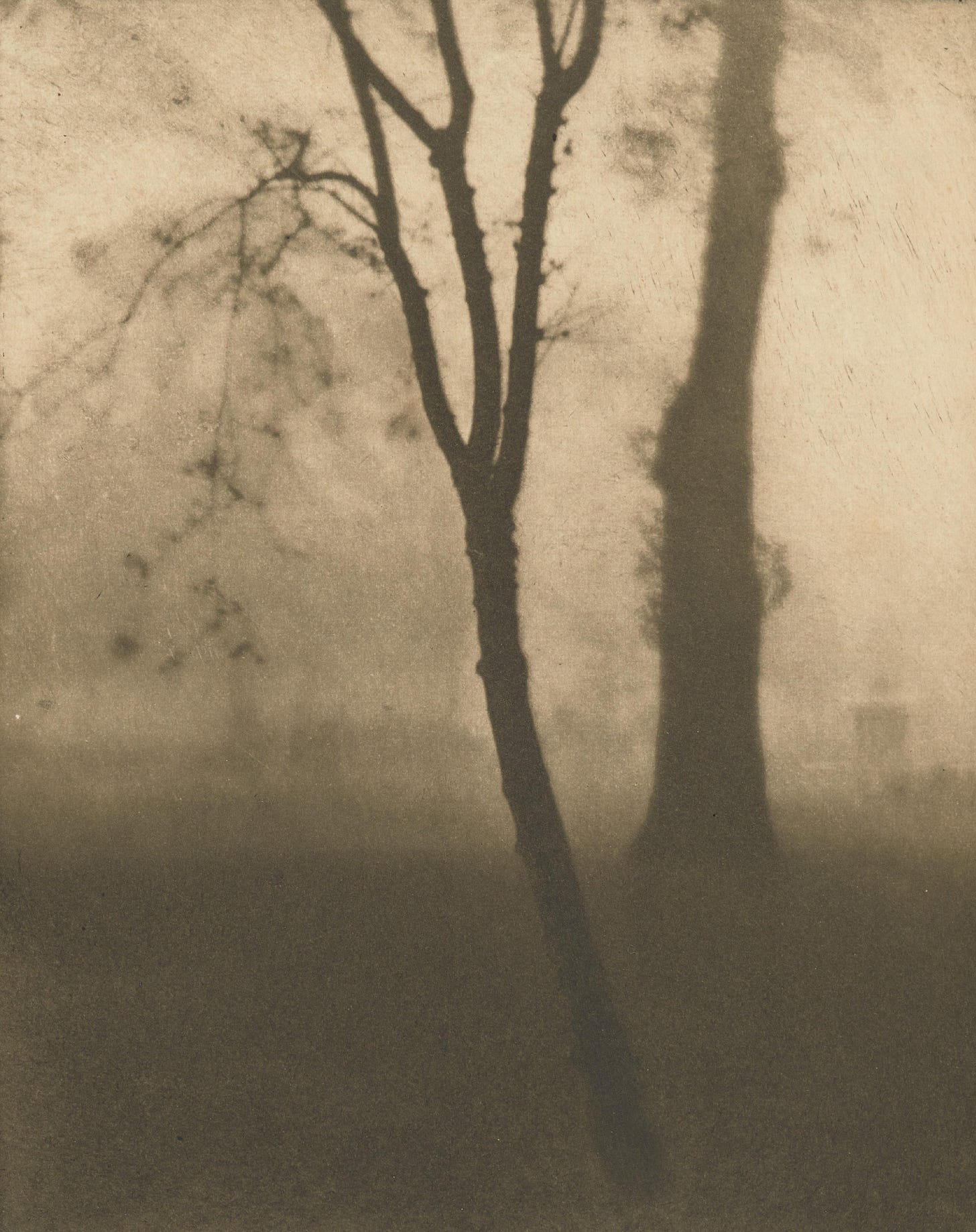

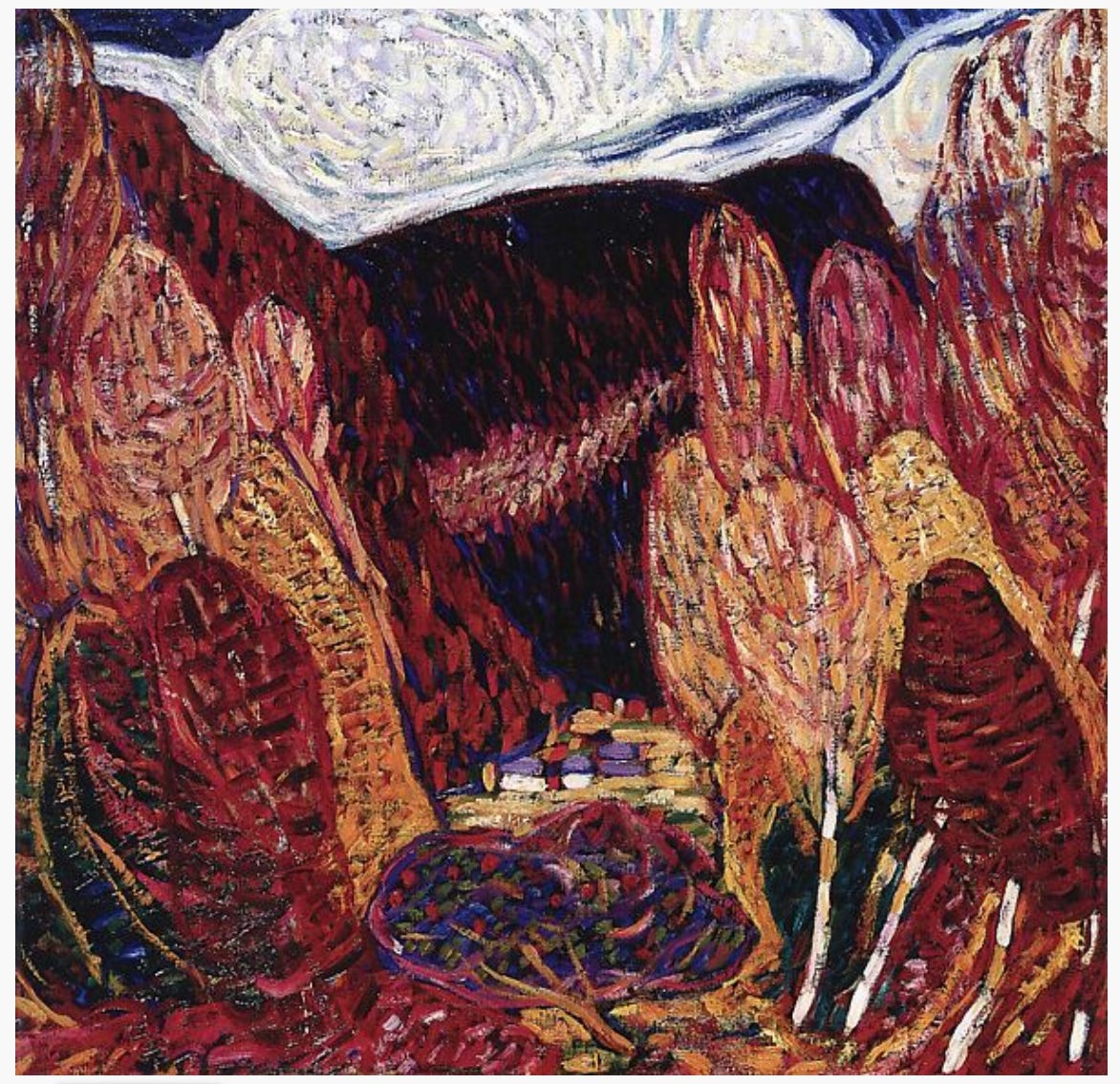

My all-time favorite autumnal painter is Maine’s own prodigal son, Marsden Hartley (1877-1943), whose misty, foliage-fueled nocturnes captured his experience with, as he insisted, only a tinge of Emerson-styled mysticism. He claimed that “true art cannot explain itself.” Yet, after absorbing the work of the post-impressionistic avant garde in Germany and in Paris in 1913, he wrote to his lifelong friend, Alfred Stieglitz, about his artistic approach. “There is something beyond intellect which intellect cannot explain—these are sensations in the human consciousness beyond reason—and painters are learning to trust these sensations and make them authentic on canvas…[This] is what I am working for.”

He was required to explain this stance throughout his career. Was his technique folk art, critics wondered? Did he paint that way because he ‘couldn’t paint’? Was he on a spiritual mission, like his friend Wassily Kandinsky? Hartley was steadfast in defining his strictly-perceptual position. This was autumn. These were the trees, and those were the mountains, as he experienced all of it. “A picture is but a given space where things of moment which happen to the painter occur…” he wrote in 1914. “The delight which exists in ordinary moments is his ecstasy…”

Speaking of scent and music (and i think there’s a term for that but can’t remember what it is), an olive oil producer i once knew, now long gone, proposed to put one of those Q code things on the label of each bottle of his oil. When you aimed your phone camera at it, it would play a few bars of music to indicate the flavors of the oil within. Need i add that this did not have major success?

You darling darling human... what fabulous sharing. Take me out of the trauma train For a moment and into sensual delight... thank you